Texte und Bilder zur Ausstellung

Herausgeber Kunstraum Dornbirn

Zweisprachig: Deutsch und Englisch

40 Seiten

EUR 15.- / SFr 27.-

ISBN 978-3940748-74-4

erschienen im Verlag für moderne Kunst Nürnberg, 2008

“Afterwards you’re all the smarter”

Reflections on Roman Signer’s “Installation – Accident into Sculpture”

by Severin Dünser

Dornbirn, August 26th 2008. Shortly after 4 pm an accident with major property damage occurred at Kunstraum Dornbirn . A Piaggio van, on a steep gradient held in place only by a rope, suddenly set itself in motion after someone near the rope had recklessly played with fire. Whereby the unmanned, three-wheeled vehicle increased its speed till, on its uphill stretch, it finally turned over and came to a halt, roof down. The water being transported on its flatbed was a complete loss. The vehicle was a write-off; no one suffered injury.

This or something similar could have been reported in the local section of a newspaper on the events that took place that afternoon at Kunstraum Dornbirn. Or like this:

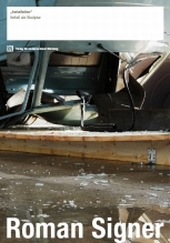

A giant wooden ramp and a Piaggio van loaded with four blue casks filled with water are the components of an experimental setup that Roman Signer put to the test in August 2008 at Kunstraum Dornbirn. The Piaggio was attached to the upper end of a steep, 11m high ramp by a rope and held its own there in defiance of gravity. Till the artist finally released its force by lighting a candle below the rope. Seconds later the rope broke and the Piaggio lurched full speed ahead, taking with it the casks on its deck. The descent of the ramp was followed by an almost overhanging uphill climb, in which the vehicle – from the weight of the casks of water – finally lost its balance and did a back flip. The momentum caused the casks to spill their contents, like a waterfall, over the ramp and the ground; the concerted action was echoed in the rush of the exiting water and resulted in the Piaggio’s landing on its roof at the ramp’s lowest point.

The contradiction in the fact that the action “Installation – Unfall als Skulptur” can be described, on the one hand, as an existential event and, on the other, as an artistic test setup is fundamental to work by Roman Signer. He grew up in Appenzell, studied at the School of Design in Zurich, the School of Design in Lucerne and the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw and developed his artistic praxis in reaction to the theories of the 1960s and 1970s that propagated the absolute self-referentiality of the object. Influenced by exhibitions like Harald Szeemann’s “When Attitudes Become Form” in 1969 at Kunsthalle Bern, by Conceptual Art and Arte Povera, his early works were already marked by a break with self-referential objects. From the beginning, Signer developed his own expansive concept of sculpture, by which the three dimensions of space as the classical function of sculpture were supplemented by the dimension of time.

The process per se became important, more important than visual appearance.[1] Signer’s test arrangements, once he sets them in motion, are free to unfold their dynamism, and what finally remains as a relic is not aimed at a readability in the sense of a classical aesthetic, but at the mental recapitulation of the foregone process (inducing a holistic perception of the artwork as an entity between a was and a becoming object).

The actions themselves consist of three parts. Part one is a test setup: research, consultations with experts and the artist’s preliminary trials lead to a, at first, static combination of different elements. The goal of the action is here already recognizable; the artist’s intention is readable from the combination of material components. An action potential has been programmed, just as much as the original state to which the viewer, after the process runs its course, will return to mentally. Part two consists in cashing in on the built-up potential by resolving and letting the process take its course. During this phase, the elements enter into a relationship with each other and subsequently undergo a change. Part three represents the result that, after the process has run its course, is left altered in form and situation. The traces left by the action allow us to recapitulate the process from the starting point to the result and, in this attempt to read backwards, to perceive the work as a temporal construction. The work is therefore simultaneously seen as an object-like structure in its manifestation and as a sculptural act in its essence.

This three-part subdivision into starting point, process and result corresponds to the narrational form of a beginning, a climax and a conclusion. At first, tension is built up by way of potentiality, so as then to introduce a change in the existing conditions, concluding in the state of an altered situation celebrated as a happy end. Narrative structure has stood the test over thousands of years, and with Signer other elements are added that additionally commit the viewer to the plot. On the one hand, by classical means that movie directors use in their films: changes that at first slowly build up (like the burning of a fuse) to then continue in a flash (like the firing of a canon triggered by the fuse). The abruptness of these changes is not only a means of bringing matters to a head in the artist’s videos, but can also be recapitulated in the relics that provide the viewer with a tool to measure the temporal span of the episodes. This serves our understanding and our interest in what is under observation, just as does Signer’s alignment of the actions and installations toward a potential replicability that tries to restrict the spread of chance,[2] thus easing the way back to the starting point.

This is therefore not about an absolute, self-referential object, nor about a pure work reduced to its concept: “With true conceptual artists, the result was mostly very unsensual. But my works are actually sensually tangible, elementary and physically present.”[3] And here we arrive back at the starting point of this reflection: the question of compatibility between accident and sculpture, between subject and object. In order to pursue this enquiry further, it is important to recall the fact that the elements Signer uses for his works are themselves highly charged: on the one hand, with their innate functions and, on the other, with the artist’s memories and projections onto which the viewers then superimpose their own associations. Vehicles, bicycles, kayaks, helicopters, ropes, tables, stools, barrels, buckets, ladders, boots, flags, paint, balloons, pistols, rifles and cannons, rockets, candles, fuses, sand, water and air are some of the elements that recur in the oeuvre and, as Signer in interviews states, are linked to memories of his childhood and youth. Growing up in a house on a river,[4] Signer in his young years experienced water not only as acoustically present but also directly as a physical force. The same goes for fire, to which Signer – whose grandfather had a factory for matches – developed a special affinity. The fact that one of his uncles was a coppersmith, another was both a commander in the fire brigade and a dealer in explosives, leads us to suspect how charged with memories the use of specific materials are for Signer. The components of the works are therefore more than universal metaphors for life; they are concentrated life experiences, archives of an artistic existence which comments on the world while simultaneously directing its view inwards. In the process the introspection is broken off in favour of a perspective that, in the end, can still hold its own as a reflection on art per se.

This reflection is one we also encounter in the work “Installation – Unfall als Skulptur”. In this case the existential factor in the work is not an object, but an everyday event. An accident is a transitory, negative occurrence, triggered by technical failure or human error, always the root cause of an accident. Formulated more generally, the control over a process is lost; subsequently, during its course, there is an unforeseeable development and an unplanned outcome. With this definition, Signer’s installation links the loss of control to the unforeseeable development (even if there is an attempt to minimize the possibilities of the action’s outcome); though the planned outcome of the run-through may in a few cases not materialize, this is not essential for the success of a work. What in most accidents is “tragic and terrible”[5] plays no role in Signer’s installation: here the journey is the destination; the test setup, execution and evaluation of the process visible in the relic are the result, thus broadly excluding artistic failure.

Signer is far removed from allegations of mischievousness; he is not interested in willful destruction, but in nothing less than a constant expansion of the concept of sculpture. Instead of a chisel, the process is the tool – in this case the accident that transforms the material into an experience for the senses and the mind. The accident deformed the Piaggio; in this way a new tool was used to bring about a common stylistic device of art. In addition, the force of the vehicle’s back flop also deformed the casks being transported, which now lie yards away from the Piaggio “as witness of a force that operates in space”.[6] With his work Signer demonstrates that things inherently possess a potential that he as sculptor transforms into a dynamic force within a three-dimensional space – similar to a painter who sets a brushstroke onto a canvas. It is an attempt to use something quotidian like an accident under the aspect of sculpture and, via the absurdity of arranging a mishap, making it tangible as an aesthetic phenomenon.

This gesture is also existentialist, and not only by making the subject in the object a metaphor (the car object suggests a driver subject). In the same way the object first becomes genuinely real at the moment of the accident, leaving behind its thing passivity so as, in its de-functionalism, to first become perceptible as being different from the functioning object and as a reality existing in real time.

The viewer at Kunstraum Dornbirn is confronted with this insight in the form of the fragments left by the action; the process itself, often perceived as a spectacle, has here been denied the public. This is what led to the work’s title: “Installation – Unfall als Skulptur”. It is an installation, not an action. The process cannot be seen in real time, only in the mind’s eye; in physical reality the recipient finds himself opposite a materiality that has been emplaced by force. Which is why this is not pure sculpture that Signer has put on display; contrary to objects, installations enter a dialogue with the room.

The relation to surrounding space is something visitors had already experienced in December 2007 in Kunstraum, namely with three actions: “Fahrt an der Decke/Ride to the ceiling”, “Aktion mit Modellhubschrauber und Fässern/Action with model helicopter and barrels” and “Kanonenschuss mit Ball auf übereinander stehende Fässer/A ball shot by cannon onto stacked-up barrels”. With these three actions, Signer first experimented with the available space and explored the installative potential so as then to conceive of “Installation – Accident into Sculpture” for the room.[7]

“Fahrt an der Decke/ride to the ceiling” consisted of a small car with the turbine of a model airplane on its back, which was propelled along the ceiling of the room while it defied gravity via the turbine that pressed it upwards (until the kerosene ran out and it fell onto the rope). Signer augmented the experience of this action by covering the floor of the hall with newspapers, which – from the breeze whipped up by the turbine – were little by little blown away till the floor was visible once again. In the “Action with Model Helicopter and Barrels”, casks (like the ones that were later loaded onto the Piaggio) were rolled across the exhibition hall by a model helicopter, which did not touch the barrels but set them in motion with air that was pressed towards the floor. At the end of the room where they came to a halt, the barrels were then stacked up to form a column. A cannon was then set up, aligned and provided with a fuse. The conclusion came when the artist stepped up to the cannon and lit the fuse. After a long, slow burn, an explosion occurred; a football was shot out of the cannon and at great speed crashed against the barrels, knocking them to the ground. “A Ball Shot by Cannon at Stacked-up Barrels” also denied the public an understanding of what took place at the moment it happened. On the one hand, because of its enormous speed, the process eluded any conscious perception; on the other, the flash of the explosion filled the room immediately with smoke. Perception was above all audible: a loud bang and the sound of the barrels being struck.

The total experience was brought on by a restriction of visual stimulation that activated other senses. This was similar to the action that preceded the installation “Accident into Sculpture” in the form of water transported in a Piaggio van. The romantic idea of a waterfall and its aestheticization at the moment of falling was thwarted by the destruction brought on by an accident. And yet the true protagonist in Signer’s work is not man, but nature: “I have an almost magic attitude towards nature; I only half finish many objects I make and want nature to continue, to somehow flow in and manifest itself. […] Nature first makes the sculpture.”[8] The actions are carried out by the forces of nature, which as constants make a recurrence and a recapitulation possible. With Signer, the experiment of an accident simulating an everyday process, at the same time, demonstrates the force of nature. Art’s appropriation of the banal by means of natural laws points in this way to the natural bent of man as liaison and liberation , to that inner conflict that you experience existentially and, as a human, above all in the dimension of time. Time passes, whether you will or not, and is the requirement for experiencing the past, but also the transitory, for “Afterwards you’re all the smarter”, as Signer remarks.[9]

[1] Konrad Bitterli, “Skulptur als existentielle Chiffre” in: Roman Signer – Skulptur, catalogue, Kunstmuseum St. Gallen, 4/12/1993 – 20/2/1994, p.8

[2] Sabine B. Vogel, “Roman Signer – Dynamis und Dynamit” in: Roman Signer, catalogue, Secession, Vienna, 7/10 – 18/11/1999, p. 11

[3] Lutz Tittel, “Gespräch mit Roman Signer im Mai/Juni 1984” in: Treffpunkt Bodensee, 3 Länder – 3 Künstler, catalogue, Städtisches Bodensee-Museum, Friedrichshafen, 12/7 – 12/8/1984, p. 86, as cited by Konrad Bitterli, “Skulptur als existentielle Chiffre”, p. 8.

[4] See the interview with Ingrid Adamer in this catalogue

[5] Ibid.

[6] Roman Signer on the installation “Fahrrad” from 1991, in conversation with Konrad Bitterli on 26 January 1993, in

[7] See the interview with Ingrid Adamer in this catalogue

[8] Lutz Tittel, “Gespräch mit Roman Signer im Mai/Juni 1984” in: Treffpunkt Bodensee, 3 Länder – 3 Künstler, catalogue, Städtisches Bodensee-Museum, Friedrichshafen, 12/7 – 12/8/1986, p. , as cited by Konrad Bitterli, “Skulptur als existentielle Chiffre”, p. 86, as cited by Roland Wäspe, “Spuren der Zeit” in: Roman Signer – Skulptur, catalogue, Kunstmuseum St. Gallen, 4/12/1993 – 20/2/1994, p. 24

[9] Roman Signer im Interview mit Ingrid Adamer in diesem Katalog

[JH1]Nicht sicher was hier gemeint ist.

Texte und Bilder zur Ausstellung

Herausgeber Kunstraum Dornbirn

Zweisprachig: Deutsch und Englisch

40 Seiten

EUR 15.- / SFr 27.-

ISBN 978-3940748-74-4

erschienen im Verlag für moderne Kunst Nürnberg, 2008