This Is Not All I See

On Thilo Frank’s exhibition Levitation by Geoffrey Garrison

There is something impossible about beginnings. Inevitably, we are unable to begin at the beginning, to get to the origin, to cut to the marrow. Our origins, by nature, remain veiled. They are as inaccessible to us as a species as are, individually, the first few, pre-linguistic years of our lives to our powers of recollection: we access our pre-history only in the form of fleeting, mute images. Memory in children develops with the acquisition of language and refinement of systems of representation, which enable us to make sense of, record, and pass on experiences in mediated form. Similarly, history begins with narrative and the ordering of significant records into an archive. The fascination with prehistory (like the child’s curiosity about birth and gestation) is an obsession with something dark and unknown.

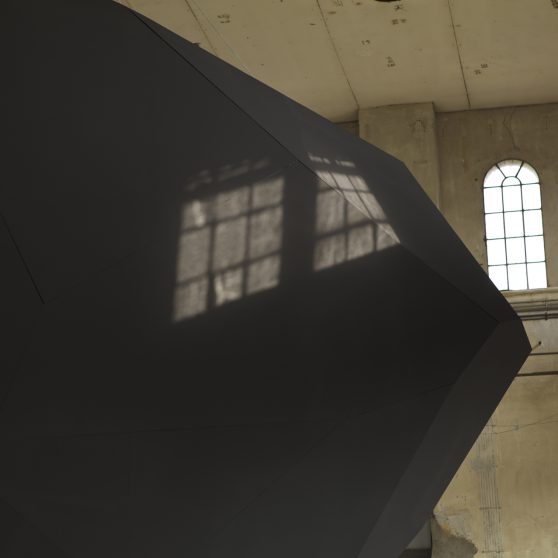

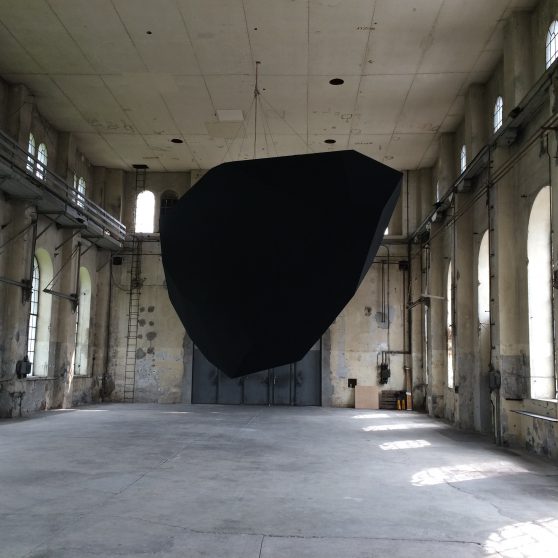

Levitation, Thilo Frank’s exhibition at Kunstraum Dornbirn, does not shy away from such weighty matters. From the ceiling of the former industrial space, Frank has hung an enigmatic, black polyhedron, reminiscent of a bulky, wedge-shaped monolith. Two-stories high and weighing one metric ton, it revolves steadily at eye level, a simple, yet effective gesture that is fundamentally surreal; we know the polyhedron is heavy, but we experience it floating above us in the unsettling zone just above our brains.

Frank derived the wedge shape of the polyhedron from the form of a hand ax, the earliest known manmade tool, a primitive teardrop blade used for hunting, butchering, digging, and chopping. The hand ax represents a milestone of sorts, cleaving man from beast and sending humans on their way to becoming homo faber, man the creator. Depending on how you look at it, it marks a beginning, cutting a line of demarcation from the animal world, or else it unleashed humanity’s true bestiality. This is the scenario depicted by Stanley Kubrick in his dawn-of-man fantasy of the first murder at the beginning of 2001: A Space Odyssey. Rather than this representation of our ur-ancestor, electrified by the monolith into a vicious bloodthirsty rage, however, the wedge-shaped stone can also conjure an image of the scavenger desperate to improve his lot in a world of scarcity. The tool is not a sign of power, but of weakness. A prosthesis for the defenseless prehistoric humans, it springs from hunger and the will to survive. It is only because early humanity had no claws, no natural defenses, that they developed tools to shape the world, construct shelter, protect territory, and claim space.

While we know that animals also use tools and that the divide between man and animal is fuzzier than we were long willing to admit, Thilo Frank’s hand ax is to be read as an extension of the human. It is a stand-in for the first art object (or at least the earliest known design object), a nod to art’s capacity for shaping the world. Enlarged, it becomes monolithic; suspended, cocoonlike. It speaks to us, in its tight-lipped way, of what we cannot know – our prelinguistic, unarchived origins.

The Echo Chamber of Memory

While the floating rock fills the space above our heads, the air around our ears is claimed sonically by a densely layered sound installation that emanates from within the monolith and is created by the space itself. The ambient sound of the gallery and the noises created by the audience – intentionally or unintentionally – are recorded live and then played back in the space are recorded live and then played back in the space. With a nine-minute delay the sound is mixed with the previous recordings and played back while the program is still recording. This process continues throughout the exhibition, layering track upon track to weave a thick tapestry of noise, marked by feedback and decay – sounding something like one might expect deep space to sound (if in fact deep space had a sound at all, which apparently it does not, since sound does not carry in a vacuum).

The sound installation recalls a similar effect created for an earlier work – the site-specific pavilion Ekko, installed in 2012, in Hjallerup, Denmark. In that work, microphones, hidden in the wooden slats that formed the twisting walls of a circular walkway, recorded the steps, comments, and errant coughs of the visitors as they strolled through the structure. These incidental sounds were conveyed around the circle from speaker to speaker, forming an unconventional echoic space. In addition, sound fragments from the past were played back at unpredictable moments, so that visitors caught ghostlike traces of others who had passed through the work three minutes or three hours or three days before.

In discussing these audio palimpsests, Frank has referred to them as archives of sounds. Yet the accumulation of sounds is not organized and sorted, but repeated, layered, and allowed to decay. Rather than a rigorous system of taxonomy, Ekko and Levitation relay more an idea of episodic memory. Snippets of the past emerge in the sound recordings in the way that reminiscences often afflict us – as a disordered, unforeseeable babel.

Through the sound components of Levitation and Ekko, moreover, the artworks reach out to the visitors and reflect them. The audience, in turn, completes the work, creating surplus, protean meanings by contributing to the soundscape’s development over the course of the exhibition. Via the sound installation, visitors are able to commune with each other and with the future.

Bombers, Mystics, and Slippers

With its sharp form, suggestive of a projectile, the enlarged hand ax communicates something threatening, something almost militaristic. Suspended in the air of the raw, industrial space, it resembles nothing as much as an airship in a hanger. Its dark, streamlined hull brings to mind the characteristic carbon black, radar absorbent paint of the F-117 Nighthawk and the B-2 Spirit Stealth bomber. Frank’s appropriation of the hand ax, then, brings us full circle, from prehistoric bludgeon to shock and awe, linking the aesthetics of modern military design, honed to produce feelings of terror and dread, to the notion of the sublime that lurks behind the figure of the monolith.

While fighter jets were designed to attain great speed, airships – blimps, zeppelins, and dirigibles – are lighter than air; they levitate. Whereas flying is about hurling through the air, levitation is about floating; it flouts the laws of gravity. This is why the notion of levitation was historically the preserve of mystics, yogis, and saints – a positive sign of divine favor or of contemplative advancement.

On a lighter note, one of the simplest ways to achieve the sensation of levitation is to climb onto a child’s swing set. This simple device has featured prominently in a number of Thilo Frank’s past works (Zwei Phoenixe treffen sich im Wald, 2006; Few Phoenixes Get Lost in Water, 2006; Reflected Phoenix, 2009; The Phoenix Is Closer than It Appears, 2010; and Infinite Rock, 2013). In the earliest swing work, installed in an underground bunker, viewers were asked to enter alone into a silent, dark room, where they would perceive, once their eyes had adjusted to the lack of light, a lone swing hanging in the darkness. The reduction of sensory input focused the visitor’s attention onto his or her own bodily experience of floating in space. Further iterations followed – most notably, The Phoenix Is Closer than It Appears and Infinite Rock, both of which invited viewers to swing by themselves inside a chamber of mirrors that extended the space infinitely in all directions and produced myriad reflections above, below, and beside them.

Yet despite their simplicity, the series of works dealing with swings are not entirely without the weight of art historical reference, although perhaps incidental. Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s The Happy Accidents of the Swing (ca. 1767), perhaps one of the most notoriously frivolous works in the history of art, is a work of simultaneously complex composition and simplistic urges; a young man, concealed in a bush, glimpses beneath the petticoat of a woman on a swing as she floats through the air, a blaze of pink amid a verdant surround, and loses a magnificently frilly slipper. Whereas for Fragonard, the pleasures are depicted within the painting’s illusionistic space (the pleasure of the woman on the swing, and the prurient pleasure of the man in the bush – presumably the stand-in for the male spectators who made up Fragonard’s audience), Thilo Frank’s swing works instead offer us a direct experience of pleasure by inviting the visitor to step into the artwork as a mover rather than viewer. In addition, they undermine the traditional voyeuristic bias of the art experience, either by negating visual pleasure entirely, in the shadows of the bunker, or by reflecting it back onto the viewer in the mirror works.

Sensory Deprivation

Crucial to Infinite Rock was the structure that housed it. Presented within a hulking black monolith in a courtyard at the Sharjah Biennial, the work evoked the Ka’aba, the cubic shrine at the center of the sacred mosque in Mecca and the destination of all pilgrims performing the Hajj; it is, in fact, the fulcrum of the Islamic world. By situating his swing installation within a setup inspired by this building, Frank embedded the simplest of pleasures within the sacred shrine, profaning the holiest of holies. The viewer – alone within the stone, on a swing, in a chamber of mirrors – encounters as an answer to the greatest of mysteries, not God, but a reflection of the self. Notably, however, what we see when we look in the mirror is again an exterior. The interior remains as far away as the furthest reflection in the infinite regress that surrounds us.

The swing in Thilo Frank’s funky Ka’aba leads me to a tongue-in-cheek – and perhaps specious – association with the floating man thought experiment, proposed by the Persian philosopher Avicenna (AD980–1037): he asks us to imagine a person with no history and no perception, created an instant ago, and suspended in air without touching, hearing, or seeing anything, not even his own body. Avicenna argued that such a person would still have an intellectual sense of self, that the soul is therefore fundamentally separate from the body. In Frank’s experiment, on the other hand, at the center of the great mystery is the exhilaration of embodiment.

The Lure

The ersatz shrine of Infinite Rock, unlike its inspiration, is not a platonic solid (al-Ka’ba means “cube”). Instead, Frank derived the irregular black polyhedron shelter from a Voronoi diagram, using it to produce a form that is reminiscent of a rock or faceted crystal. In Levitation, too, the hand ax functioned as a means for the artist to create a shape that he would not normally invent and that defies visitors’ expectations. Conventional forms, Frank says, can be comprehended immediately, whereas an irregular structure encourages viewers to move around, animates them to change positions in order to understand the work’s many faces.

Similarly, Levitation activates visitors by gesturing to a hidden interior that they cannot access. The sound coming from within the hanging polyhedron indicates that something perhaps is concealed inside. The object is all the more inscrutable because it cannot be entered. Levitation, in this sense, is a lure. By mystifying viewers, Frank draws them in, piques their curiosity, and sets them in motion. The meaning constantly withdraws and returns, suspended, in distorted, fleeting echoes. There is a central thing that remains veiled – perhaps, judging by the cryptic titles of his earlier works, the quiescent phoenix, about to be reborn.

Thilo Frank’s work does not shy away from mysteries and heavy questions. And yet it leaves them unanswered, to be puzzled over, and ultimately enjoyed in a simple, direct way. Beyond the references, associations, and thoughts it inspires, there is the corporeal encounter between object and viewer, the solid experience of the monolith in space.

Interview with Thilo Frank

Thomas Häusle:

The emphasis of the exhibition projects of Kunstraum Dornbirn in the 2014 programme is on the conditions of perception. In your projects, spaces within spaces are often the focal point; the objects have the character of built-ins that completely alter the original space and, above all, the spatial perception, and often dynamise it. Where does this almost architectural passion to read and change spaces come from?

Thilo Frank:

For me, to begin with, it’s interesting to start solely from our perception. We’re constantly moving in spaces, that is, the object is itself interesting for me when I put space in relation to it. I always start with the viewer or museum visitor and think it’s very important always to include the surroundings, no matter where the formulation of the work takes place; only in this way can I create a shared or an individual space, by being able to take up or separate several viewers. There are works of mine in which access to them is conceived of for only one person at a time, a very intimate and individual experience.

Thomas Häusle:

As in The Phoenix Is Closer than It Appears, in that the swing can be used by only one visitor at a time?

Thilo Frank:

Exactly. It’s also interesting for me to incorporate a ritual, as in the work Infinite Rock, which I showed in Sharjah (UAE). You have to remove your shoes before entering; you walk on mirrors, and know that someone else is also in there because other shoes stand outside. Once you’re inside, you really focus only on yourself in this work, and are the only point of reference in the space.

Thomas Häusle:

Spatial perception, light and form are obviously important in your work, but are supplemented again and again by sound and dynamics.

In all your projects light plays a central role. I think of the installation Ekko from 2012, but light is also the viewer’s focus in the projects in sacral space in Denmark. The installation Infinite Rock, a project at the 2013 biennial in Sharjah, was a black polyhedron with mirrored walls inside. In our current exhibition project, Levitation, the object is also a matt, jet black-pigmented polyhedron. You speak here of the intended absorption of light. The contrast between the reflection and absorption of light repeatedly determines your projects.

Thilo Frank:

For me, the theory of perception here plays an important role. What models masses, what models our environment visually? For us, it’s primarily light. Only through light and its reflection can I experience my surrounding space. This filter has immense influence on the creation of our world. If I exclude light, I can then prune and focus. I also incorporated this in earlier works. One of my first swing works was an acoustically isolated space; it was completely dark; you could enter only one by one and it took about thirty seconds before you could recognise something. After a certain period of adaptation, you see a white board, then two ropes. In this situation you’re called upon to take an initiative. Similarly in my bunker project, eight metres underground. I set myself the task of expanding the spatial dimensions, and this was possible by trimming them in terms of perception so as to give cognition a larger scope.

Thomas Häusle:

Can we also see Levitation and other of your projects as archives, as treatments of the past and present?

Thilo Frank:

Yes, I can say, as a sort of review of my own works, that they can be read at various levels. If I look through the filter of an art historian, I try to put things into pigeonholes, and this is in fact very close to my way of thinking – very self-referential. For me it’s always very important what was there before, or more simply, what every work comprises. What is now being newly created always has a pre-history. I think it’s important to incorporate this thought in my own work, to take it up as an intensifier. I don’t necessarily have this unique view – I look into the past, the future and exist in the present – but rather I try to mix several levels, and it’s exactly this interplay that I find so incredibly interesting.

Thomas Häusle:

It seems that it’s first the combination and diversity of sensory perception that motivates and inspires you.

Thilo Frank:

When in an installation, or actually a situation, I address several senses, the work and the viewer’s experience of it can leave a deeper and more lasting impression. It’s things that pull us out of our everyday lives which have a lasting impact. When I address various levels of perception, I have a better recollection. Our memory is being constantly re-archived and the present is always exercising influence on it. I find it interesting how we talk about our past, how I talk about a work from memory, and also how people who visit the exhibition talk about it and try to pass on this story. While working on a project, I already think about what stories with what narratives could arise from it.

Thomas Häusle:

In your latest work you treat the polyhedron formally as a constructive element and aesthetic object. What idea, what meaning, do you associate with this historically and mystically charged form? Does the treatment of this form and the choice of the polyhedron represent a specific development in your work?

Thilo Frank:

For me, I think it’s a kind of formulation to break out of Euclidean space. As viewer, I have to enter into action to understand the form, that is, I try to tend to be a bit ‘off’ the Golden Section or the aesthetic harmony because in this situation I can then quickly grasp the whole object with a first look. For me it’s really more a matter of the viewer having to feel out the object, to surmount a distance and occupy various perspectives in order to make it understandable. The polyhedron is therefore interesting because its form is irregular. Moreover, it’s historically highly charged, and in Levitation it’s formed based on the function of a hand-axe, and so stand for our development. In terms of cultural history it’s important because it could represent a pithy crossroads in the development of man and animal. For me it’s a total archetype. In my recent works, this form comes more from the field of generative architecture, where I determine the parameters so as to mould the form, the complexity of whose process of formation I can no longer cognitively keep up with.

Thomas Häusle:

This is also the principle of construction for the object at Kunstraum Dornbirn. If I’ve understood it aright, it’s a generative, almost architectural model, which can be changed at various points and recalculated based on these changes.

Thilo Frank:

Yes, to begin with, a principle of construction, which makes it possible for me as an artist constantly to develop the aesthetic design without beforehand having to think about the changes in the construction. It’s important for me what image, what situation, I have at the end. To give myself over to this experiment as an artist, to have components or parameters, to be able to change them, to be able, that is, to generate the form playfully out of this process, fascinates me. For me it’s extremely important to have this process; only through it can I carry on a dialogue with the form, develop it so far as before I was able to do only in a reduction. If you think back further into history, to Brancusi, for example, who strove after a reduction, I can here go so far as to produce a complete explosion of complexity, which I wouldn’t otherwise have been in the position to realise.

Thomas Häusle:

Back to the polyhedron. How important for you is the fact that the ‘magic’ of the black polyhedron instils in the viewer an expectation of something mysterious, something hidden and valuable?

Thilo Frank:

It’s certainly one of the components I play with. There’s always a horizon of experience, actually a stance of experience, and if I want to make someone curious about something I first try to hide it. I want to lure the viewer and bring him or her into a cognitive and, indeed, physical situation. I find this black body, which is at home in the history of so many cultures and in the history of religion, which serves, so to say, as a container, incredibly interesting. Whether it appears in popular culture in science fiction films or as a monolith in Stanley Kubrick, it’s invariably interesting how this container is staged.

For example, the Kaaba, which even though we know what it looks like inside and the rituals to which it’s attached, always remains a mystery. I wonder where this feeling comes from and why mankind creates such objects in the most various cultures. For me it always has to do with self-reflection, that is, nothing else is at home there than me myself, but I need it as a kind of antipole in order to carry on a dialogue.

Thomas Häusle:

Museum visitors or users are regularly more than passive observers in your works; the public becomes an integrative and even constitutive component of them. Your works and projects become expressive and complete only through the active participation and engagement of the public. Where do you want to lead the public, of what do you want to make them aware?

Thilo Frank:

I tend to create this situation and everyone then has his own experience of it. Of course, I can visually lead or pave a way by setting these guide lines. Through these installations I attempt to re-evaluate things, break them out of patterns and build a new relation to some all-too naturally accepted values and spaces, including, for example, social spaces. It should be a mental stimulus.

Thomas Häusle:

Participation is a very strained and, in its various forms, over-exercised concept in contemporary art. Some artists and above all theorists go so far as to call for participative approaches already in the development phase of a work. What understanding of participation and engagement of the public do you integrate in your works?

Thilo Frank:

It strongly depends on the work. I’ve done works that emerged from competitions or that, because of invitations by community authorities or intuitions, stood from the start in a dialogue with people in a particular place. As here, when I was invited to Dornbirn, I had a particular place – this already defines the social context. In some way or another the people here have a part in finding the form. It’s different with the work itself; here the local public is a component, but not the sole component. Without the viewer the work can’t be communicated, but also vice versa, and a productive process emerges only in the combination of both.

Thomas Häusle:

In your current project Levitation, you build the consciously or unconsciously made noises of the public into the work as an integral part. The visitors repeatedly transform the work during the entire duration of the exhibition and first complete it, so to say. How openly and actively is this transformation through the public inherent in the work? How far do you actually allow for this transformation?

Thilo Frank:

Transformation takes place as a component. The work is charged up by the public. Of course there’s always the question of where the transformation begins and where it ends. For me, the viewer is very important in the archiving of the work, or in the story that weaves itself around the work and continues to create its context. When someone tells me about an object, a space, an experience, I can participate in it through my capacity for empathy; then we’ve come full circle. Here’s where it becomes interesting for me. You could go so far as to say that everything here in the exhibition isn’t really important any longer, but only what I experience, perhaps not even that which I experience through myself, but rather through the others who tell me about it.

Thomas Häusle:

The most exciting things are often hidden. The space-dominating object develops a changing, yet always determining presence, thus playing itself to the fore. But the true greatness and profundity of a work emerges in the interior, in the invisible. I’m tempted to say that your objects often seem to be receptacles, vessels for something more important, something nonmaterial, also something somehow mysterious. Why is the real information, the real statement in your works so spectacularly sheltered and concealed?

Thilo Frank:

Maybe it’s a kind of protection for me; or, to put it in other words, for me it’s more about the question I pose in space, because I don’t have answers. I can formulate the question through the object; only each viewer can him or herself give the answer. I’m also very careful about making a statement, because I think it’s a pity to hedge in the pluralistic experience and to prefabricate an answer in the whole context. Quite the contrary, I think it’s very exciting, and naturally has a certain “wow” factor, to attract attention so as first to broach the question and not necessarily to expect an answer. As an artist, you’re always observing, searching, rather than finding answers.

Thomas Häusle:

Playing with inner and outer determines both the aesthetics and the tension of your work. You skilfully play with the eternally significant theme of form and content. In your work form and content seem usually very detached from and independent of one another. Nevertheless, the content can emerge only in and through the respective form. How determinative is this relation of form and content for you really? How strongly does it determine your intended artistic statement?

Thilo Frank:

For me form and content are actually concepts that always go together, always run parallel, and this is a development that always has various emphases and shows itself in the formulation of the thought. Finally, I can’t get outside my perception, that is to say, it’s the work that depicts my view of the world, I can’t separate the form from the content. The thought is already the manifestation of the form. For me, it’s an approach; there can of course be several approaches, and I find it hard to break down or chop up this process. The formal concepts flow, and in the end I can’t get outside my perception.

Thomas Häusle:

Every nine minutes in Levitation noises in the room perceptible to the microphone are simultaneously played back and recorded. Then the respective sound passages are saved and transferred to the sound carpet consisting of all the previous nine-minute soundtracks. The result is a sound archive that contains all the sounds of the entire exhibition. Present and past change, overlap and influence one another every nine-minutes – a really powerful image. How far is the conviction that the past co-determines the present deliberately built into your work and important for it?

Thilo Frank:

It’s very deliberately built in, because I arrange the microphones technically so that feedback, a delay or an echo results, so that it’s not only recorded and played back with a time delay, but what’s played back is also again recorded.

An important aspect of my work is the question: How does our perception and our memory work, and what conscious or unconscious actions does it posit? These processes shape our view of the world. People always make the stories they will have.

Thomas Häusle:

What’s next in the dynamics of your work? What projects and development may be expected from Thilo Frank?

Thilo Frank:

Exciting ones, I hope!

There are quite a few dialogues and projects in process. I had several offers to work with institutions, something that particularly interests me. It’s like here in Dornbirn – that is, I’m free to work without technical restrictions, and can also completely let myself go in the work itself, a sort of carte blanche. There are also some ‘art in architecture’ projects on the drawing board for next year, and I hope it will continue to be exciting and challenging.

Thomas Häusle:

Thank you for the conversation.

Translated by Jonathan Uhlaner