Katalogdokumentation mit Fotos zur Ausstellung und Texten vonThomas Häusle und Freek Lomme.

Herausgeber Kunstraum Dornbirn

zweisprachig Deutsch/ Englisch,

56 Seiten,

erschienen im Verlag für moderne Kunst Nürnberg, 2014

ISBN: 978-3-86984-099-4

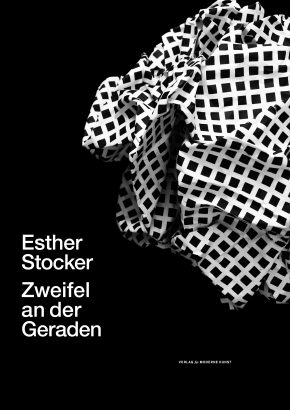

The Italian artist Esther Stocker examines the requirements of perception under reduction of the perception field on a black/white grate pattern. This is equally as prevalent in her paintings as it is in her installations. The grids themselves are the central focus and are a sufficient components of their own to complete their own artistic image and perception. The project in Kunstraum Dornbirn depicts the most recent expansion in her series and transforms the assembly hall into a experimental space of perception.

Esther Stocker, born in Silandro, Italy, lives and works in Vienna. Studied at Akademie der Bildenden Künste, Vienna; Accademia di Belle Arti di Brera, Milano; Art Center College of Design, Pasadena, California. Numerous exhibitions in Italy and abroad.

Winner of the Otto Mauer Prize in 2004.

TH: This year’s programme of Kunstraum Dornbirn is captioned with the motto “Conditions of Perception”. Your project opens the exhibition year at Kunstraum. How much are perception and especially conditions of our perception the conceptual basis of your artistic statement on the one hand, and its sensory transmitter on the other?

ESt: A sensory transmitter – I have to think at once of Kant, who speaks of sensory knowledge. Yes, I do think that perception is the key to the world. Perception enables access to other people and the environment in general. This is my basic material in art and, of course, also includes thinking. For me the connection of seeing and thinking is very important. Seeing and understanding form a unity for me.

TH: So certainly in the sense of a conceptual basis, that this is the actual constituting ingredient of your artistic work.

ESt: Yes, reflection on perception is a part; I can work with this and produce objects. For me this forms a unity – on the one hand, my own experience with works of art and the inspiration to fabricate something unknown or to encounter something unknown; on the other hand, to produce the object. I’d say this forms a unity.

TH: The quality of the faculty of human perception is strongly determined by the phenomenon of pattern recognition. Your ‘”crumpled ball” objects put us in an equally playful and compelling state of application of and, at the same time, reflection on this sensory capacity. To what extent does this quality of perception represent only the function of a cognitive bridge leading to your “true” artistic concerns – because it’s obviously not enough to recognize only the superficial?

ESt: Yes and no: all the questions are acted out on the surface. Is there something behind it? I’d say that pattern recognition begins with the figure of basic seeing; this consists of simple building blocks, though it very soon becomes complex. A distinction is made between low level and high level vision: when you recognize something immediately, it’s ‘low level’, and when you begin thinking about what you see, it’s ‘high level’. Or when something more complex builds up and you use cognitive structures to grasp it better. Still, it’s not clear to me that you can separate the two levels in this way, because there are also complex questions in low level vision, visual phenomena that you can’t quite explain – for example, forms that at first glance look like black squares in a certain clustering or having a certain variability which nevertheless already touch the limits of perception.

TH: In mentioning the black squares you’ve gone into something that I’d like to deepen. The orthogonal grid, black and white planes and lines, is a ubiquitous and defining feature of your visual representations. Visually, you reduce your expressive reservoir almost completely to these abstract elements. On a closer look at your works, however, some trifle very often interferes with the superficial order of the statement. This confuses the viewer. To what knowledge should the resultant illusion lead?

ESt: This deviation or leakage of a sign, in this case of a wrinkling or an absence of a form or of shifting a form, is a strong aesthetic sign, which indicates that a form can possess both order and disorder, and so can be a visual and a logical paradox. It can have a strict rhythm and, at the same time, be incomprehensible. Here I’m interested on the one hand in where the unknown meets the known, and on the other hand what defines what. Does the unknown define the unknown, or does it define the process? Or, as I’d have it, does it function only as a unity, is it a formal and visual paradox, which you can get at in language only with difficulty because you very soon reach the limits of language. Visually, at any rate, it’s a strong sign. I have great confidence in these forms that can demonstrate a formal paradox and only be approximated in language.

TH: You just spoke of order and disorder, of grids in every conceivable form, which can assume even ordering functions. Grids bring order to expression and themselves take on an ordering function.

ESt: Can I butt in here briefly? It depends on the standpoint. When I began my work, the grid served as a comprehensible functional ordering system. But it’s also the case that the grid can be very confusing and bewildering, since memory can get lost in the uniformity. Imagine you’re walking through a completely uniform architecture: you wouldn’t be able to remember where you were. A grid can also generate disorientation. Then there’s the abstract grid, the grid of ideas, or the grid as rhythm, as in music. So I think the grid is so general a system, which has such different functions in so many areas, that you can conceive of it both as an ordering system and as a not quite comprehensible form.

TH: The fascinating aesthetic appearance of your works seems strict, ordered and clear. The presence of order is as evident as your playing with this order. Above all, geometrical patterns of order become visible. What do these geometrical orders stand for? At what orders or disorders are the references pointed?

ESt: The geometrical orders stand for an imaginary world in my works and are perhaps part of a fiction. A geometrical order is actually the greatest possible contrast to an individual. I once used the quotation: From the point of view of geometry, all directions in space are equal. This is a simple, comprehensible statement. In geometry, it works as an abstract idea, but for me, as a person, space can never be totally equal; I can imagine that, but I can never actually carry it out. As an individual, I find myself at a point and must make decisions. It’s also a temporal process. I’m not myself a grid that functions as an abstract principle. So in a certain sense a geometrical order is also a fictional world.

TH: Whether as an exercise in rage or with intent to deceive, your current series of works, Knäuel, came out of the physical destruction of a geometrically unambiguous, two-dimensional starting-point. To what extent are you interested in the deconstruction, and beyond it especially the construction, in this destruction?

ESt: Let me describe the process again. I have a piece of paper and I crumple it. There are two factors: an action and simultaneously a destruction. So not a complete destruction, rather a deformation. Here, then, the two concepts, construction and destruction. If you look at the construction more closely, it’s actually a destruction. This is a fascinating subject and a philosophical question – what is the whole and what the part? Do I destroy a sand pile when I manufacture a brick, or is the brick destroyed when it falls apart? If you think the concept of construction through radically, it contains destruction. In this sculpture, the theme of crumpling and folding, which has also occupied other artists, is important to me; that the basic structure is quite monotone and robust, and also that there’s a tension between the constantly identical grid and the known square or the straight line, to show a kind of arbitrariness and incomprehensibility that proceeds from the simple gesture of the hand, which is important because the hand is an instrument of the visual, but also stands for the cognitive. So the hand as a connection to the brain, as an instrument that executes its work immediately, the thinking hand, which creates the visual, aesthetic sign.

TH: In the act of destruction, of the supposed destruction of rectilinearity and the previously mentioned order, and in addition to its obvious physicality, the object gains above all in its potentiality as a statement. You verify the operation of human patterns of recognition and show us at the same time the limits and weaknesses of this perceptual phenomenon. To what extent is the resultant, possible cognitive process compelling as a constitutive component and driving force of your work?

ESt: The cognitive process is actually the centre of my work, but also for the people with whom I can share my work. I would say it’s a cognitive process and a process of experience. Experiences that you have in the encounter with these objects. Maybe in order to make something that I find unintelligible intelligible. And it’s also of course a game, a testing, an intellectual playing with forms. I think: What can these forms do or how strong is their own life, what can they do with me, they don’t belong to me after all. I can’t control the statement they make. What effect this will then have, or whether it will really create confusion, or whether it will make a completely different aesthetic statement – this is the fascinating thing, that the artist can’t control it one hundred per cent. There are always surprises.

TH: In this connection I ask myself what order is being vicariously destroyed, what clarity is being sacrificed to the gain in knowledge, what disguise is being removed, what deception is being laid bare and what expectation is being disappointed?

ESt: Mine actually, my own order. And it’s my own expectation that’s being changed. Order is something partly learned; there are processes that you’ve learned, which are also quite useful and which makes things comfortable for you. It’s like the way from A to B, that it doesn’t occur to you to take the straight path, but rather to branch off. The aim is to break my own order and alter my own expectations.

TH: If we transfer this to the current exhibition situation and project it onto the viewer, then his own order and own expectations should be called into question or call themselves into question in the reflective process.

ESt: I see this really as a unity, because the art work belongs to the viewer as well as to me. I see this very general abstract language as a certain means of distancing, but only in connection with an almost existential experience. That it goes back again to the individual, that again and again it’s a very simple encounter with the forms, because order is always the order of a person.

TH: You don’t yourself speak of illusion when you lead the viewer astray, have him perceive a curve as a straight line. You call this ‘vagueness’. What does the term ‘vagueness’ mean in the context of your work?

ESt: Vagueness could be the approximate, the imprecise, and stands in contrast to the very precisely defined, high-contrast, geometrical forms and grids that I see as the foundation of my work. They should also be considered under this aspect. At first glance, the forms seem to be robust; the fascinating thing is what happens when a small change or shift or wrinkling gives them a different identity. Best of all an identity that can’t be immediately classified. Then a clear form can appear unclear; that’s what I would describe as vagueness. I have even basic doubts about the stability of terms or forms; I therefore use these robust forms in order to show this.

I like it that there are limits of comprehension, of perception, and that these can be felt. Vagueness is a certain weakness, but this weakness can also mean freedom.

TH: What significance does the very present and precise aesthetics of your work assume in the context of your work’s statement and impact?

ESt: It’s my own fascination; I’m myself fascinated by what these forms can do, and of course it’s also my artistic tool. In the sign language that I prefer to use lies a secret for me too. The simpler the unities, the more difficult they become to describe or to say something meaningful about them. The aesthetics of my work is for me a trust in the forms, that they are meaningful for me and that I have the confidence that this sign will affect the viewer quite directly.

TH: In the “Knäuel” series, you carry out a strategic extension of your image, object and form language. After the two-dimensional technique of painting and the transformation of these paintings in space in the form of spatial installations or, more accurately, interventions, it’s become sculptural. What is the significance of this step in development for you, what possibilities has it opened, and how aware were you of this development taking place?

ESt: The development wasn’t planned; I didn’t think, ‘Now I’ll make sculptures’; on the contrary, I otherwise probably wouldn’t have done anything. I’d been meaning for a long time to make the skin of a space with a wrinkle; I’d already built models in my studio, but they didn’t work for technical reasons, and perhaps also for aesthetic ones. Through rethinking this, I came to sculpture; I did a photo series with the wrinkled models, and then I realised they could be sculptures. It grew in steps from a smaller to a larger dimension; at present I think it could actually further develop into a small-sized architectural situation, in a pavilion.

TH: The title of the exhibition, the current exhibition in Kunstraum Dornbirn, Zweifel an der Geraden [i.e., Doubts about the Straight Line], directly addresses the loss of order, the breach of expectations. To what extent should this doubt provoke a questioning of attitudes and world views?

ESt: It’s as it is with me; I’d wish the visitors too the immediate experience of an almost daily struggle. This is in fact related to the title of the exhibition, Zweifel an der Geraden. As I’ve said: Is the simplest way from A to B the shortest, or does it make more sense to take a detour? The simplest doubt consists in not taking this path, or it’s the doubt whether this is really the shortest way. The doubt about the straight line can also be more complex: Does the straight line exist at all? It’s the doubt about something that’s a simple guideline, but needn’t be the case. This can come from everyday life, but can then also extend into an overarching theme.

TH: Those are very beautiful closing words. Thank you for the interview.

Translated by Jonathan Uhlaner

Katalogdokumentation mit Fotos zur Ausstellung und Texten vonThomas Häusle und Freek Lomme.

Herausgeber Kunstraum Dornbirn

zweisprachig Deutsch/ Englisch,

56 Seiten,

erschienen im Verlag für moderne Kunst Nürnberg, 2014

ISBN: 978-3-86984-099-4